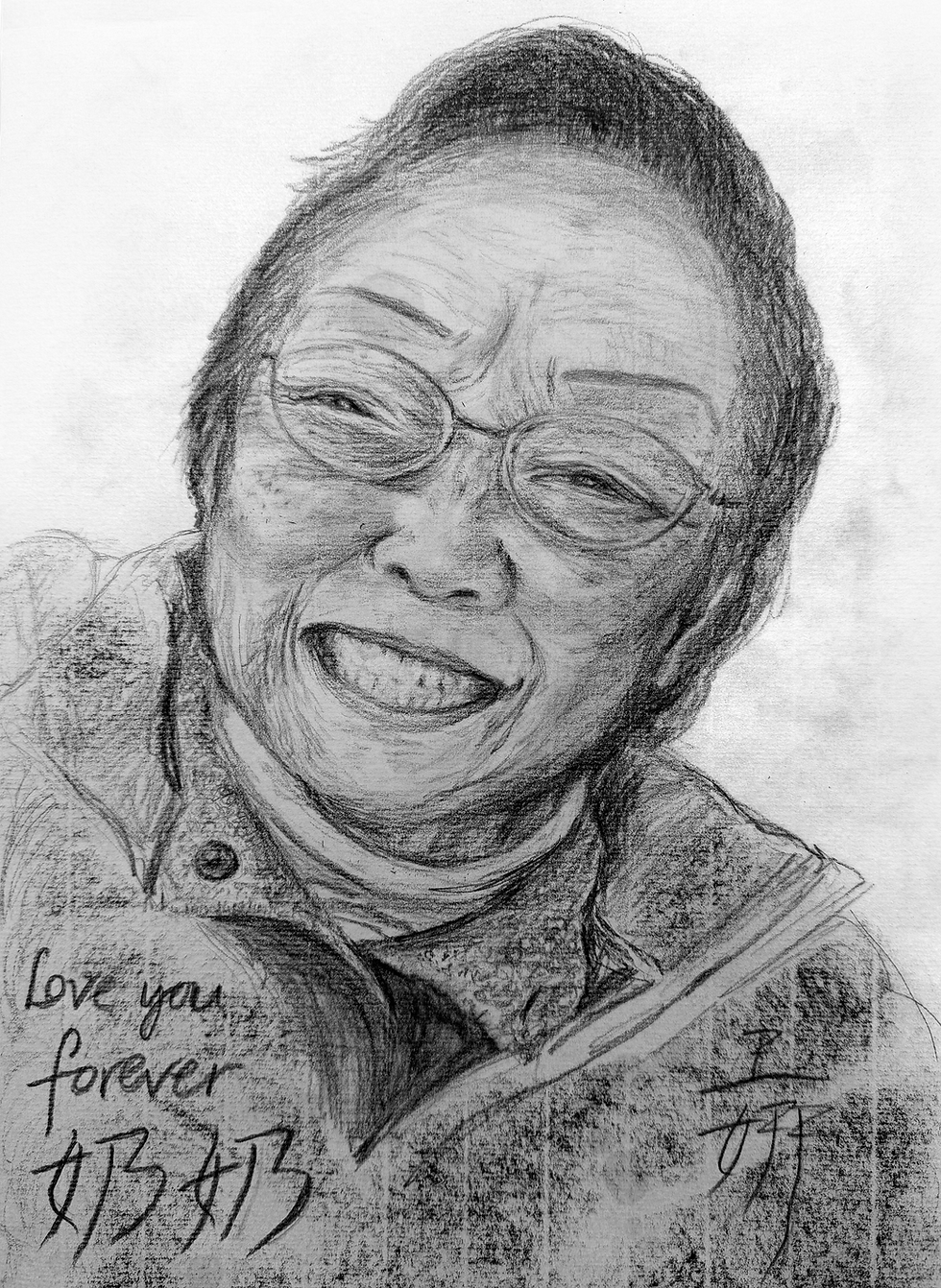

Remembering Nai Nai

- Dr Em Wong

- Oct 14, 2025

- 5 min read

My grandma Nai Nai (奶奶) celebrated her 106th birthday in May and died on August 29, 2025. She died as she had lived: tenaciously, relentlessly, and fiercely drawing her family together. Her love and resilience will continue to shape our future generations.

Early years

My grandma Nai Nai was born in 1919 in the city of Changzhou in Jiangsu province. Nai Nai was The Girl Who Lived.

After having lost six infant sons in a row before she was born, her parents hailed her birth as a turning point—a sign that their streak of bad fortune was finally changing. Normally the birth of a baby girl would not have been cause for such celebration in 1919, but she was their lucky star. She was even nick-named Li Di (莲第), meaning that the next sibling would be a little brother—and he was. Great-uncle Jerry Liu not only survived infancy, but lived to be 102 years old.

But infant deaths were extremely common in those days. Of the 16 babies born to Nai Nai’s mom Tai Po (太婆 ), only Nai Nai herself and three brothers survived to adulthood. Nai Nai would describe to me with horror how she had witnessed one baby sibling after another stiffen up with cramps and die.

Nai Nai told of how Great Grandpa Liu (Tai Gong 太公) had tragically lost his father at an early age but managed nevertheless to overcome incredible odds by becoming a successful textiles boss. Nai Nai grew up in and around textiles factories, learning how to build community among factory workers while helping her mom to supervise factory canteens.

Tai Gong was impressed by how much more refined Japanese fabric was, compared to the coarse woven material available in China. So in the 1930s, he sent his most promising young engineer Cha Chi Ming to Japan to learn about modern textiles manufacturing. Nai Nai was married to that engineer in 1936 at the tender age of 17, and he became my grandpa (Gong Gong 公公).

Small but mighty

Nai Nai’s first baby was a girl who died in infancy, developing a fever and becoming rigid with cramps as her siblings had done. One can only imagine how helpless and devastated she must have felt, to watch her own baby sicken and then succumb. No wonder Nai Nai was also so fearful of cramps later in life, even though she went on to have seven healthy children.

Nai Nai never spoke of that first baby, but would tell instead of running from bombs that would rain down from the skies in wartime, which was all the time. She was hustled away from the big city threat of military conflicts, far into the rural hinterlands of Sichuan province. One of her favorite stories was about how she arrived on that first night to her new home in the Chongqing factory housing. It was derelict, primitive, and infested with rats and fleas.

Nai Nai grew up learning how to build community

My grandparents returned to Shanghai briefly at the end of World War II, but the turmoil in China was not yet over. Tai Gong sent them off to Hong Kong to start yet another textiles factory in 1948. Nai Nai remembers jealously guarding two vats of expensive chemical dye during the barge journey, which would be required to begin their new production line. She once told us grandkids the story of how Tai Po had sewn gold rings into their clothing so that they could be smuggled out of China, and then showed us that she still had the rings, 60 years later!

Nai Nai was truly a force of nature. She measured maybe 4’10” at her tallest, but her mighty presence and tremendous courage was felt by any and all who met her.

Growing up with Nai Nai

My earliest memories of Nai Nai are not so much around specific events, but rather an impression of quick, bustling energy, and affectionate warmth. She was constantly surrounded by the village of her clan, who were also her closest friends and social circle. She loved nothing better than being in the midst of a laughing and lively crowd of family.

When I was old enough to travel with Nai Nai, I remember her wanting to practice English with me, having me help her pronounce words like “California.” She was forever carrying around tiny notebooks in which she would make me write down vocabulary words for future review. Like any immigrant kid, I took it completely for granted that I was supposed to serve as translator whenever needed, even though my Chinese was barely adequate.

Nai Nai would tell me stories of what it was like to raise seven healthy children. She spoke of the stress and worry of keeping good wet nurses for each infant but sometimes having to improvise with goat milk for feeding in a pinch. She was also committed to scraping together enough material each Chinese New Year, so that each child could have a new handmade outfit and cloth shoes.

Nai Nai loved nothing better than being surrounded by the village of her clan

Nai Nai was never one to sit still. Wherever we went, she would busy herself by sorting through all the cabinets and drawers, endlessly reorganizing and rearranging piles and shelves of stuff. She would carefully inspect every corner and plant in the garden, fretting over bits that weren’t behaving themselves. She also loved the freedom of driving herself everywhere on American freeways, and I was her constant companion, as she explored new neighbourhoods.

I’ve come to appreciate how lucky I was to have grown up surrounded by her treasured artwork. Tai Gong had been a renowned art collector in China, and Nai Nai had inherited his love of art. Bold calligraphy scrolls jostled for space with classic landscapes on the walls of her home, and intricate Asian carvings nestled comfortably alongside Western bronzework and majestic African forms.

Remembering as she forgot

Nai Nai began losing her memory around the time that Gong Gong became sick with cancer in 2006. It began innocuously enough and was written off as being linked to worry, then later as a grief response after he died. Even as a doctor, it took a long while for me to accept what was happening to her.

She had already been living with dementia for almost a decade in 2017 when she suddenly forgot who I was. I distinctly remember how horrified and surreal it was to have her treat me as a stranger. She was polite but distant, hosting me as she would a stranger in her home, hinting that she was busy and so it was time for me to leave. It still hurts to recall how devastated I felt leaving her house that day, knowing that the house I’d grown up in would never be the same without her.

Nai Nai taught me what it means to work hard and to believe in myself

Of course, her memory and ability to remember loved ones fluctuated as her condition progressed. And as she gradually lost the ability to take care of herself, our roles reversed as she became more childlike, needing help with dressing, bathing, toileting, and eventually feeding. I would bring her shiny jewelry and toys to make her smile, and engage her in connecting with facial expressions as she became increasingly nonverbal.

I was no more than eight years old when I first said that I wanted to be a doctor. No one else believed I could do it. My own mother told me kindly that maybe I could marry a doctor instead. But Nai Nai always believed in me and wouldn’t let me be discouraged.

Nai Nai has taught me what it means to work hard, be resourceful, and to believe in myself. I will forever be grateful to have been able to love and care for her, and to have learned so much from our extraordinary matriarch.

Comments